Take the path to model-less multivariable control

Get the latest trends and improvements in level and flow technologies

Manual multivariable control

Multivariable control is usually considered a product of the computer age, but nearly all processes are multivariable, and multivariable control has always been with us. In the pre-computer age, multivariable control was carried out by the operating team, who adjusted controllers and valves manually to keep related process variables within constraint limits and at economic targets. This basic approach to managing the multivariable nature of most processes remains a prominent aspect of plant operations today, whether in lieu of, or in conjunction with, modern automated multivariable controllers.

That's a step on the path to model-less multivariable control – to reflect that it's always been with us, albeit in manual mode. Ergo, automated model-less multivariable control should also be possible, and should bring all the benefits of timeliness and consistency that normally accrue with any automation, even if it doesn't bring 100% of the benefits deriving from the use of models (although that is by no means being conceded at this point).

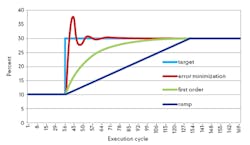

Figure 1: "Error minimization" is industry's de facto control performance criteria, but achieving it is characterized by relatively aggressive control action. In industrial process operation, managing risk and preserving process stability are usually higher priorities, so that a first order or ramp approach to constraints and targets is usually preferred.

Model-based multivariable control (MPC)

With the advent of computers in process control, it became possible to automate multivariable control, with (as mentioned) obvious potential to improve the quality of constraint control and optimization. Industry, armed with promising model-based theory and new-found computer power, opted early on for the model-based path. But several associated assumptions have played out unexpectedly (1):

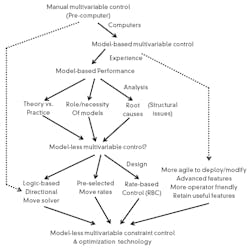

Figure 2: A prototype model-less controller design utilizes gain-direction, a logic-based move solver, pre-selected move rates, and "rate-based control" (RBC), in place of model-based methods, to determine variable moves.

Nobody had yet realized that "error minimization," industry's de facto control performance criteria, would prove inappropriate for many multivariable control purposes. For high-level constraint control and optimization, less aggressive and more careful control action, with an eye to managing risk and preserving process stability, is usually preferred from an operations standpoint (Figure 1).The general consequence of this—of industry's commitment to a technology that has not matured as expected—has been stasis. Instead of the cost and complexity of MPC coming down, they remain high. Instead of performance improving, it remains low. And instead of evolving a more affordable and agile tool, suitable to the everyday needs of a plant operating environment, MPC remains an inflexible and taxing technology to own. Meanwhile, countless medium-range multivariable control applications throughout industry remain unfulfilled for lack of such a tool.

Figure 3: The path to model-less multivariable control derives from historical manual multivariable control, from the emerging structural limitations of model-based technology, and from recognition that industry needs a more affordable and agile solution. In the end, model-less multivariable control emerges as a viable alternative technology, rather than a compromise, standing on its own merits.

Acknowledging a degree of reality in this view—that due to the structural nature of the limitations, MPC is unlikely to soon become cheaper, easier or more effective, and that meanwhile a large share (perhaps the lion's share) of advanced control applications remain out of reach for lack of an appropriate tool—is another step on the path to model-less multivariable control.

Model-less multivariable control

It is this combination of circumstances—the attractive prospect of a common-sense, model-less multivariable control technology deriving from historical manual methods, juxtaposed against the experience of expensive, difficult and often underperforming model-based technology—that compels the end user to consider the former. However tantalizing the prospect of dispensing with models may be, it is the long road of experience, not the shortcut of simplification, that compels one to consider the model-less path.

Upon embarking on this path, one is initially apprehensive that it may become an exercise in pure compromise, as less perfect methods are contrived to overcome the lack of models. But the results of an initial prototype design are encouraging. Taking into account the following design criteria, model-less technology emerges as a potentially viable alternative technology, rather than a compromise technology, standing on many of its own merits:

- Glean the wisdom and experience reflected in historical manual multivariable control methods.

- Find technically sound alternatives to the emerging complex lessons of model-based multivariable control performance (as given above).

- Achieve the theoretical and practical high level of multivariable control and optimization performance as historically promised by model-based technology.

- Provide a more affordable, agile, scalable and robust multivariable control tool to meet the needs of industry.

Figure 2 is a simplified top-level view of a prototype model-less multivariable control algorithm. In place of detailed models, model-less technology uses only gain-direction (the most fundamental and reliable aspect of models). Instead of complex math, it uses logic to determine the direction of variable moves. Move rates, rather than being dynamically calculated, are preselected based on safety, procedures and experience. And a novel technique called "rate-based control" (RBC) is used to complete the move sequence in a manner that lands controlled variables on constraint limits and optimization targets without overshoot or oscillation. This approach captures the above design criteria. For more information, look for Part 2 in the February issue.

References

- Multivariable Control Performance, InTech, July-August, 2014.

- Small matrix model-less multivariable control, Chemical Engineering, February, 2014.

Download our beginner's guide to differential pressure level transmitters

About the Author

Allan Kern

P.E.Consultant

Leaders relevant to this article: