How history, principles and standards led to the safety PLC

Farhan Batvaz, C&I designer, Foolad Technic International Engineering Co., can be reached at [email protected].

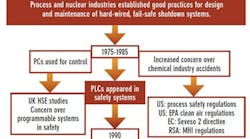

The process industries often deal with large quantities of flammable, explosive and hazardous chemicals, and they have a long history of incidents resulting in lost lives, lasting injuries and environmental as well as property damage. Experiences gained from these have led to the use of safety instrumented systems (SIS), whose sole purpose is to maintain plants in safe condition. SISs have evolved over time, and numerous safety-related standards have been written to specify their design and implementation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Safety instrumented systems (SIS) have evolved over time, and numerous safety-related standards have been written to specify their design and implementation.

Safety instrumentation is not exclusively an instrument and control engineering subject. Successful implementation of an SIS project depends on knowledge of other disciplines, as well as a well-defined safety management system within the company. Without proper support structures and a good understanding by all involved in defining safety requirements, safety instrumentation on its own will be unlikely to deliver the levels of safety expected of it.

SIS structure

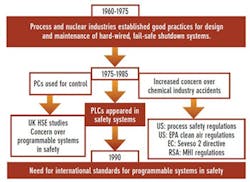

Figure 2: The SIS is designed to be a separate control system that acts independently of personnel or other controls such as the basic process control systems (BPCS) or fire and gas (F&G) system.

SISs are control systems that take the process to a safe state on detection of conditions that may be hazardous in themselves, or if no action were taken, could eventually give rise to a hazard. SISs perform safety instrumented functions (SIF) by acting to prevent the hazard or mitigate its consequences. Alternative names for an SIS include trip and alarm system, emergency shutdown system, safety shutdown system, safety interlock system and safety-related control system.

Note that the SIS is designed to be a separate control system that acts independently of any other controls or personnel, such as the basic process control systems (BPCS) or fire and gas (F&G) system (Figure 2).

SISs are normally regarded as being structured in three parts: sensors to measure, detect atmospheres, and determine process and equipment online conditions; a logic solver to evaluate the plant conditions, make decisions and output signals; and actuators to execute the required actions. SISs also have interfaces to users and other control systems to send shutdown and safety commands.

Safety integrity levels

The degree of confidence that can be placed in the reliability of the SIS to perform its intended safety function is known as its safety integrity. The concept of safety integrity includes all aspects of a safety system needed to ensure it does its job. One of these aspects will be hardware reliability and the way it responds under all conditions. Other aspects include the accuracy of the design and the level of understanding of the hazards that went into the design.

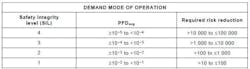

Safety system engineers recognize it's helpful to grade safety integrity into four distinct bands of risk reduction capability known as safety integrity levels (SIL). Figure 3 shows how four SILs are recognized and how these levels encompass four ranges of risk reduction factor (RRF) capability.

[sidebar id =4]

The required RRF provides a scale of performance for the ability of a safety system to reduce risk. We can use RRF as a measure of safety integrity.

The safety requirements of the application determine the SIL that must be met by the entire system. It follows from the structure of the SIS that all three subsystems must individually be good enough to ensure that overall safety integrity meets the intended SIL. This is a useful concept because it means we can concentrate on each subsystem separately at the basic engineering stage.

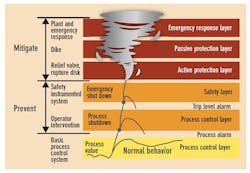

Figure 4: The SIS is only one layer in the plant’s total risk reduction strategy, which can be fully described by a layer of protection analysis (LOPA) where each of a number of safety measures work together to prevent potential incidents.

The SIL 1 safety system is the most commonly used, and provides risk reduction in the range from 10:1 to 100:1. In the process industries, the highest SIL rating normally used is SIL 3. SIL 4 is only used under very special circumstances such as nuclear plants. SIL levels 1 to 3 represent a coarse scale of safety performance for the SIS. The challenge is to specify the right SIL for any particular problem.

Protection layers

The SIL is chosen based on the required level of risk reduction, but the SIS is only one layer in the plant’s total risk reduction strategy. This strategy can be fully described by a layer of protection analysis (LOPA) where each of a number of safety measures work together to prevent potential incidents (Figure 4). Protection layers can be divided into two main types: prevention layers that try to stop the hazardous event from occurring, and mitigation layers that reduce the consequences after the hazardous event occurs (Figure 5). Examples of prevention layers include:

• Plant design: Plants should be designed as far as possible to be inherently safe. This is the first step in safety, and techniques such as using low-pressure designs and low inventories are obviously the most desirable route to follow wherever possible.

• Process control and work procedures: The control system and the working procedures for operators play a role in providing a safety layer since they try to keep the machinery or process within safe bounds. However, their contribution to plant safety is limited and can sometimes be overrated.

• Alarm systems: These have a very close relationship to SIS but they don't have the same function. Alarms are provided to draw the attention of operators to a condition that is outside the desired range of conditions for normal operation. Such conditions require some decision or intervention. Where this intervention affects safety, the limitations of human operators have to be allowed for.

Figure 5: Protection layers can be divided into two main types: prevention layers that try to stop the hazardous event from occurring, and mitigation layers that reduce the consequences after a hazardous event occurs.

• Mechanical or non-SIS protection layers: A large amount of protection against hazards can often be performed by mechanical safety devices such as relief valves or overflow devices. These are independent layers of protection and play an important role in many protection schemes.• Shutdown systems: The SIS provides a safety layer by taking automatic and independent action to protect personnel and plant equipment against potentially serious harm. The SIS doesn't require a response from an operator.

Using more than one method of protection is generally the most successful way of reducing risk. The idea of protection layers and successive risk reduction is only valid if the layers are fully independent of each other. It assumes if one layer fails, the other layers will still do the job. If there's a possibility that two or more layers could fail at the same time, the assumptions become invalid and the protection systems are said to have a common cause failure. {pb}

Standards are clear

Until the 1980s, the codes of practice for design and use of trip and alarm systems were set down by major chemical and petrochemical companies. Their codes of practice established most of the ground rules used today. They provided a solid and well-proven technical basis for essentially hardwired, logic safety systems based on analog sensors or direct acting switches, and using relays or hardwired, solid-state modules for logic solving. The codes of practice served industry well, and became the starting point for standards to allow more industries and equipment suppliers to use and provide suitable safety systems and components. These include the IEC 61508 and IEC 61511 standards (Figure 6).

[sidebar id =7]

IEC 61511 explains in its introduction that it's to be used by those who are managing, designing, implementing or operating a SIS application in a process or similar plant. The safety equipment they may have to buy should be engineered in accordance with IEC 61508. We should use IEC 61511 for plant safety projects and use 61508 for design and manufacture of safety system products. IEC standards are finding worldwide international approval. In particular, IEC 61511 was developed in cooperation with U.S.-based companies and the ISA. In the U.S., it's published as ANSI/ISA S84.01-2004 (IEC 61511 Mod).

IEC 61508, Part 1, was released in 1999, and later parts were released in 2000. The standard was the result of more than 10 years of committee activities and represents a comprehensive attempt to cover all aspects of the design and operation of SIS using programmable electronics. The principles laid down in this standard are widely applicable to functional safety systems in any form of industry.

Standard vs safety PLCs

Safety PLCs have become the dominant form of logic solver over the past 10 years through their ability to provide shared logic solver duties for many safety functions in one SIS. Safety PLCs are developed for their tasks through the provision of extensive diagnostic coverage using internal testing signals operating between scanning cycles of the application logic. The PLC detects its own faults and switches into a safe condition before the process has time to get into dangerous condition. The software of a safety PLC is developed to have a range of error detecting and monitoring measures to provide assurance at all times that the program modules are operating correctly. The application programs are developed with aid of function block or ladder logic languages, where each function his tested for robustness and only limited configuration options are available.

One major objection to safety PLCs has been their cost, and this is a problem for small plant applications. This is gradually being addressed, and smaller, cheaper units are now available. IEC 61511 also makes provision for safety-configured industrial PLCs. In some plants, it's been common practice to use a standard, industrial-grade PLC for some trip system tasks. This is unlikely to be compliant with IEC 61511.

Standard PLCs initially appear to be attractive for safety system duties for many reasons, such as low cost, scalable product ranges, familiarity with products, ease of use, flexibility through programmable logic, availability of good programming tools and good communications. However, standard PLCs have significant limitations in safety applications, such as they're:

- Not designed for safety applications;

- Limited failsafe characteristics;

- High risk of covert failures (undetected dangerous failure modes) through lack of diagnostics;

- Software reliability issues (also stability of versions);

- Flexibility without security;

- Unprotected Communications; and

- Limited redundancy.

The IEC standards require that programmable systems have information on measures and techniques used in the design to prevent systematic faults being introduced in hardware and software (including the PLC system software). The requirements are likely to be in excess of those available in standard industrial PLCs. Industrial PLCs aren't generally required to have high levels of protection against random hardware faults because they depend on basic reliability to be sufficient for the industrial control user. The problem with a PLC in safety is that the hardware isn't exercised frequently, so failed output states or stuck program loops will not be revealed as easily as they are when a machine stops or a continuous control loop goes wrong.

The SIS designer has to provide adequate coverage for many types of possible dangerous failures, and this is what a manufacturer does when it builds a safety PLC. IEC 61511 provides for using a safety-configured PLC in SIL 1 and SIL 2 applications. However, there are stringent requirements, and the standard requires that we meet the conditions for prior use, just as we must with an instrument. Generally, these requirements are beyond the scope of the average PLC user, but it may be that conversion of some PLCs can be achieved at an economic advantage where a large population exists.

In the safety PLC, the entire logic solver stage from input to output is duplicated, and if one unit fails, its diagnostic contact will open the output channel and remove that unit from service. The SIS function then continues to be performed by the remaining channel, while the faulty unit is being repaired. Notation “one out of two” (1oo2) applies because the system will still perform in the presence of one fault between two units. The parallel connection of the two units substantially improves the availability. Note that diagnostic performance is further improved by cross-linking between the CPU of one channel and the diagnostics of the second channel.

This PLC logic solver forms the brain of an SIS. It will provide the central point for the engineering of all functions required from SIS, and all critical trip functions will be kept secure through the program protection features. It will require some investment in time and training for the plant technicians. It's important to proceed carefully with the selection of the logic solver product for a new project because this is going to be a long-life item. It may require a considerable amount of expense over the years to ensure the product support and its software are available to the plant. However, most users of safety PLCs seem to find that the integrity the whole trip system is improved when compared with relay-based trip systems by virtue of having all the logic functions in a controlled software format.

When selecting a logic solver, always look for the complete hardware and software package to be from the same manufacturer and always ensure that it's available with certification for at least the highest SIL that you intend to use in your applications. The certification should always be to IEC 61508, and it should cover the hardware, operating system, programming tools and safety manual supplied with the product.

The following is a statement on this article from William (Bill) L Mostia, Jr. PE

1. Figure 3 probability of failure on demand averages & RRF ranges are incorrect (see below table). The author has left out the ≥ & ≤. The table title refer to "Probability of Failure on Demand (PFD)," which should be "Probability of Failure on Demand Average (PFDavg)," which are very different.

Source: Draft of Table 4 IEC 61511-1 Edition 2 ( used for ease of pasting into this document and has not changed from 61511-1 2004).

Also, as a result RRF's: 100, 1000, & 10,000, 100,000 are excluded from the table; similarly for the equivalent PFDavg.

Also, the author refers to "SIL Degrees Table" and I am not sure "degrees" is a generic term for this. It might be better stated a "SIL Levels Table," even though "Levels" is embedded in "SIL."

2. The author's Figure 1 left out the development of the S84 standard, which began in 1984 when ISA founded the S84 committee, which cumulated in 1996 with the issue of this standard (the first for a SIS) and acceptance by OSHA as RAGAGEP. The IEC standards for SIS also began in the same time frame as S84 and not in the 1990's. IEC 61508 came out first in 199902000 but IEC-61511,however, did not come out until 2004 (when it was "harmonized" with S84). If anything, it was in the early 1990 that people began to realized that there was more to SIS than just the PLC. In addition, he left out the contribution of the seminal safety book Guidelines for the Safe Automation of Chemical Processes in 1993 by CCPS and that the second edition of this book should be out this year. The author mentions the first edition of IEC 61508 (1999-2000) but fails to mention the second edition, which came out in 2010, or the fact that the second edition of 61511 is in the final stages and should be out this year or early next year.

3. The author's Figure 2 is misleading in that he refers to safety being separate from the BPCS yet connects his SIS sensor to the same process connection as the BPCS sensor.

4. The author seems to be rather down on the use of general purpose industrial PLC, yet it can be viable choice many times for simple SIL 1 systems, especially for small companies where the investment barrier of a safety PLC may be a substantial. While some of the safety PLC manufacturer are offering more modular systems, they still ain't cheap and the level of support required can also a barrier. There are also legacy industrial PLC's still percolating along out there. The problem with the industrial PLC (and for that matter for the safety PLC) is not so much with the PLC but the potential for systematic errors, e.g. people. A general purpose industrial PLC are very reliable (e.g. AB, Modicon, etc.) and can be utilized for a SIL 1 application and meet the standard 61511.

5. Page 45, last paragraph states: "IEC 61511 explains in its introduction that it's to be used by those who are managing, designing, implementing or operating a SIS application in a process or similar plant. The safety equipment that they may have to buy should be engineered in accordance to IEC 61508." This is not stated in the introduction of 61511-1 nor is it a specific requirement of 61511-1. It is only one of two method of equipment selection in 61511-1 (Clause 11.5.2.1).

6. The author does discuss redundancy a bit but fails to mention that a key concept regarding redundancy is hardware fault tolerance (HFT).

7. I think that cybersecurity should have been mentioned especially with the upcoming requirements in 61511 and that a "security risk assessment" will be required by the standard.

8. The author's description on a safety PLC as having redundant channels is not quite correct as single channel safety PLC's (1oo1D) are available.

9. The author puts great emphasis on the safety PLC when it failure contribution is less than ~10% of the SIS failure continuum of sensors, logic solvers, and final elements. Field components represents the balance ~90%. The safety PLC may contribute ~80% of the potential systematic errors.

10. The author's discussion does not have much on systematic errors or human factors in SIS systems and their minimization, which is an increasing concern as people have started to realize that SIS hardware is very reliable when properly designed and that systematic error and human factors have to be addressed to achieve overall safety. This is one of the primary purposes in the 61511 lifecycle (also not mentioned in the article).

11. The author doesn't mentioned the developing "safety controls, alarms, & interlocks (SCAI)" in ISA 84.91.01-2012 and in the CCPS book " Guidelines for Initiating Events and Independent Protection Layers in Layer of Protection Analysis," where requirements for non-SIS instrumented safety systems will be under increasing scrutiny and that more requirements will be probably appearing in future standards.

12. I felt that the author did not credit ISA as a leader in the SIS effort historically and currently (this may be a bit of a US centric view point but there is plenty of evidence to support it). As part of a discussion of issues currently facing SIS, the author failed to mention the eight ISA 84 technical reports. While these are not normative standards, they are authoritive and discuss developing key issues regarding SIS and safety systems such as SIL calculations (TR 84.00.02 - new edition will be coming out), testing (TR 84.00.03), SIS Implementation (TR 84.00.04), burner management systems (TR 84.00.05), safety fieldbus design (TR 84.00.06), fire and gas systems (TR 84.00.07), wireless (TR 84.00.08), & the new Security Countermeasures Related to SIS technical report (TR 84.00.09).

While I realize that this must have been intended in a brief introduction but I felt that there were areas where this article could have been improved.

Leaders relevant to this article: