Key highlights:

- Hedengren's journey from academia to industry and back demonstrates the critical importance of applying theoretical control concepts to real-world chemical plant operations.

- The article showcases a scalable model of training using low-cost microcontrollers, an idea that process engineers involved in training or workforce development can adapt for their teams.

- The emphasis on smarter, data-driven systems aligns with the future of process engineering.

John Hedengren never expected to teach process control. As an undergraduate in chemical engineering at Brigham Young University (BYU), he wasn’t planning for post-graduate school at all. However, thanks to a textbook he used during a senior-year process control course, his direction quickly changed.

The book, Process Dynamics and Control, by Dale Seborg, Thomas Edgar and Duncan Mellichamp, piqued his interest in control so much that he thought that he’d found his passion. The book captivated him enough that, noticing Edgar was at the University of Texas-Austin, he proposed that he come to Texas and work with the well-known process modeling expert and 2007 Process Automation Hall of Fame inductee.

“Tom said, ‘I don’t know who you are, but send me your resumé,’” Hedengren recalls. He sent his it, and soon moved to Austin to work with Edgar and pursue a Ph.D. “That’s how I got my start in process control.”

And it led to a career of accomplishments and Hedengren’s own induction as a 2025 Process Automation Hall of Fame member.

Experiential learning

Teaching still wasn’t in Hedengren’s sight when he graduated from UT-Austin. Instead, he went to PAS Inc. in Houston, where he developed first-principles models for homopolymer and impact co-polymer polypropylene reactors. He also conducted advanced process control (APC) training for internal and external clients.

From there, he went to work for ExxonMobil in plant automation services, and quickly found himself working in Houston, Europe and Saudi Arabia on advanced controls. “Coming out of school, seeing some of the theoretical, and then shifting quickly to working on commission controllers in large chemical plants shaped my ideas about control and what's useful in practice,” Hedengren says.

While he liked the work and the people at ExxonMobil, he was drawn to his work with graduate interns and engineers based, not only in Saudi Arabia, but also Singapore and Europe. He began teaching short courses to other engineers while in the field. It was then that he knew he wanted to return to academia, and what better place than BYU, where he started.

Returning to Provo, Utah, nestled among its scenic Rocky Mountain peaks, Hedengren pondered what type of professor he wanted to be. His industry experience taught him that hands-on learning is often more productive. “Coming from industry, I wanted my process control class to be based on experiential learning, where students could get their hands on a controller,” he says.

Temperature control lab

Hedengren quickly figured out it was hard to schedule 100-120 students to go into a lab to work with the equipment. So, he took matters into his own hands—literally. He assembled a small board microcontroller, and had his students build versions of it themselves. But the idea wasn’t sustainable.

“It’s pretty complicated [for the students],” he admits.

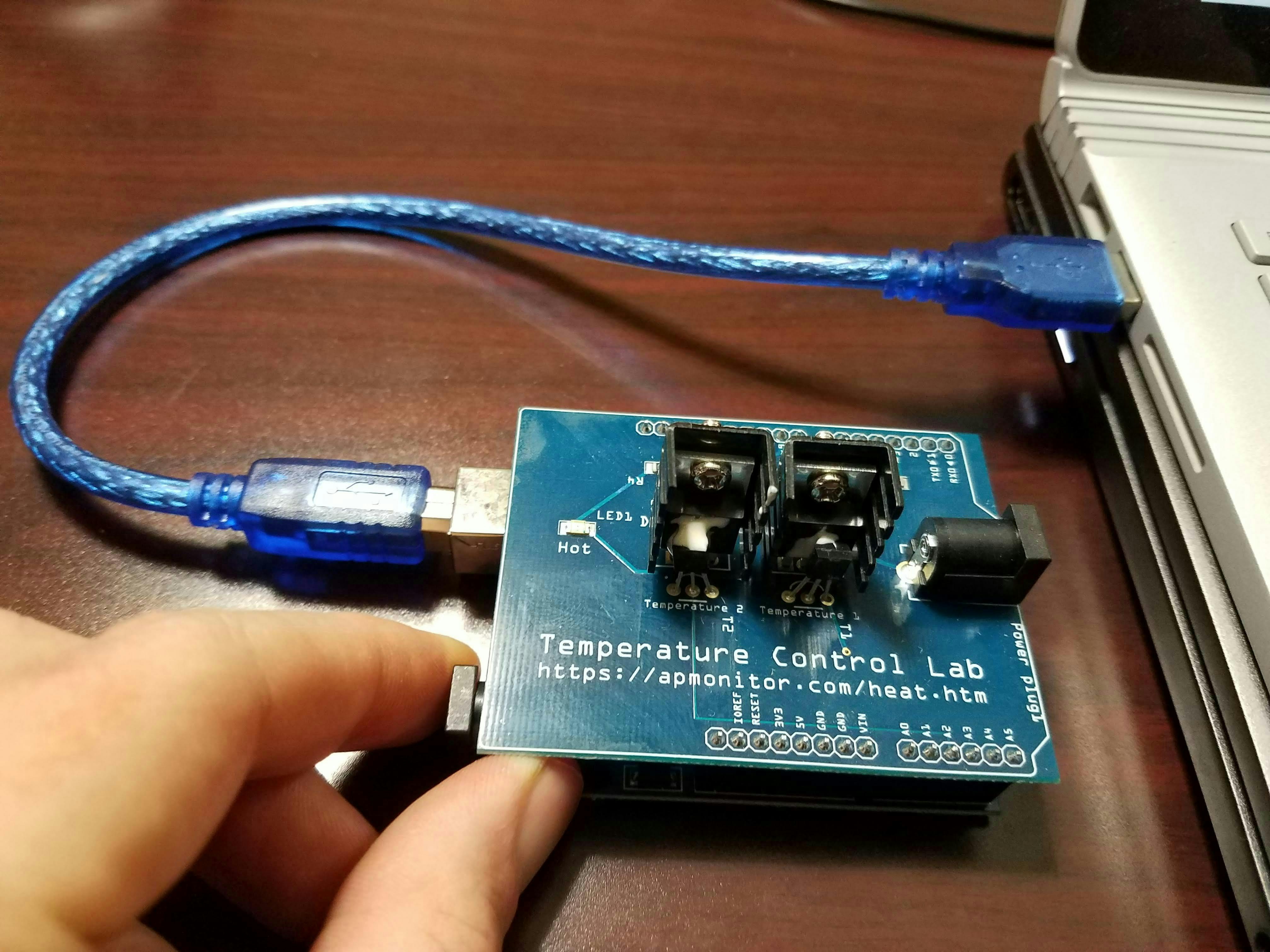

Instead, he and a few other process control professors put in a bulk order for microcontrollers to equip their own classes, and reduce costs through volume discounts. The idea took off, and today it’s known as the Temperature Control Lab.

“It’s a small temperature control lab device, and we’ve now produced about 12,000 of them,” Hedengren says. “It’s used by about 100 universities and thousands of industry professionals to learn how to tune a PID controller, how to step test, and how to do system identification.”

The current device is the result of collaboration between professors, researchers and graduate students. He lauds one of his students, Abe Martin, as instrumental in developing and writing the initial software.

Hedengren is also chair of the IEEE Control System Society’s (CSS) Technical Committee on Control Education, and he’s collaborating with researchers there to further develop the devices as a learning tool. The goal is to create modular experiments that can be simply plugged in, and given to every student.

Get your subscription to Control's tri-weekly newsletter.

Running with control

A former All-American collegiate athlete, Hedengren not only knows his way around a control loop, but also around a track or a cross-country course. He’s passed those running genes and skills down to his children as well. His daughter, Jane, is one of the top high school distance runners in the U.S. She set four national high school records this year, placing her as one of the best in high school history.