This Control Talk column appeared in the December 2018 print edition of Control. To read more Control Talk columns click here or read the Control Talk blog here.

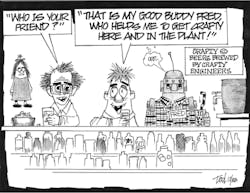

When my friends and relatives ask what I do, I say that I am a process modeling and control engineer. This draws blank stares, so I say I help measure and control flow, pressure, level and pH, hoping they can relate to this based on their thermostat, tub, sprinkler and perhaps pool. They’re not very impressed, so I tell them I have written many serious and humorous books, and cofounded a Mentor Program for the International Society of Automation. I can detect with some, particularly those not in the tech industry, that “automation” is viewed negatively as taking away jobs. This was most evident in a hospital room when, after a high-tech heart procedure, the heart specialist asked what I did. As I started to explain how I improved automation in the process industry, the guy in the next bed, who had the same procedure, interrupted and said to the doc, “He is one of the guys helping take away our jobs with robots.” The heart doctor replied, “I’m looking forward to using a robot.”

I tell potentially more altruistic people that automation makes industrial processes safer and more efficient creating less waste and providing environmental protection. Increasing production does not seem to be important to them.

Steve pointed me to an eye-opening paper, “The Multiplier Effect,” by Keith Nosbusch and John Bernarden (Manufacturing Executive Leadership Journal, March, 2012, p. 48). It shows how “smart manufacturing” by automation creates millions of jobs each year, an order of magnitude more than the jobs displaced. What a great term. Who can argue that they want “dumb manufacturing?” Also, you can ask, “Do you want to be doing a repetitious job, or one that is interesting and encourages creativity?”

Here, we ask Steve to help us gain the incredible perspective offered in this paper. How do partnerships with universities and companies doing research and development foster high-skill and high-wage jobs?

Steve: Thirty-plus years ago, globalization was the answer to cutting production costs through cheap off-shore labor, process automation was at the stage of the first smart electronic transmitters, and factory automation was starting to replace relays with PLC logic. Companies thought the logistical complications and quality control issues that arose from cheap labor were worth the risk. The resultant damage to the U.S. middle class made the public skeptical of industry in general with the exception of the roller coaster oil and gas sector. Fast-forwarding to today, I find it ironic that there are hundreds of thousands of skilled-labor jobs, many of them in automation, going unfilled because we don’t have the talent available yet to fill them. We fight political battles about the minimum wage to grab headlines when automation workers are needed to continue the rise of domestic manufacturing. There are very few automation-related university programs for engineers, for some reason a unique situation in the U.S. Without a clear career path in process or factory automation, our primary mission is to create partnerships with universities and industry. Accreditation agencies are not particularly interested in advancing new engineering degree programs outside the traditional verticals without strong influence from industry and academia.

Greg, you wrote recently about that very effort by you and Dr. Kelvin Erickson, Dr. Peter Ryan and Chris Toarmina at Missouri S&T. I contend that there is an industry ROI available in nurturing automation coursework as a minor within the engineering vertical, in Dr. Erickson’s case, BSEE. Current hiring practices by Fortune 100 companies looking for automation talent involve chemical, electrical and mechanical engineering grads designated for automation work, and require a minimum of three years of experience before being productive in that field on the job.

Greg: There are more than a dozen different companies supporting a modern automation system. I am in R&D for one that specializes in simulation, the key high-tech means of improving operator and system performance by procedure automation and advanced control. Dynamic models have been the source of knowledge discovery and deployment throughout my career, as seen in the Control articles “Virtual plant virtuosity” and “Compressor surge control.” The office I work in has a history of hiring a dozen or more interns representing more than 25% of their workforce each year. Most of the hires for a permanent position to build dynamic models have been from these students. Since first-principle models build heavily upon understanding the process relationships and interactions seen in automation systems with digital twins on actual projects, the new employees almost immediately can significantly contribute to virtual plants for operator training systems and process control improvement.

Operators appreciate not having to deal with stressful, complex, unfamiliar situations requiring immediate attention. While operations may first be skeptical or concerned about state-based control or advanced control, once they see how much better and more recognizable the operating conditions are by repeatability from automation, they are very appreciative and supportive. A key part of success is making sure all such improvements are thoroughly tested, and operations and technical support including maintenance are thoroughly trained and can see the benefits through online metrics. Companion improvements to the operator interface are essential, so that operations and technical support are completely aware of what the automation system is doing, and can intervene when necessary and appropriately adjust and continuously improve the system. Failure to do this can lead to system failure and complete removal of this automation, making it nearly impossible to make any future improvements of a similar kind despite new knowledge and expertise gained.

I can readily see how the tremendous increases in the flexibility and capability of instrumentation and controls raises the role and capability of everyone involved in the process industry, including all of us working to supply, install, maintain and improve automation systems. How does advancement in automation increase the number of jobs created through the multiplier effect?

Steve: Any time another specialty within the field is created thanks to new technology or conclusive results of research projects, it increases the scope of work and expertise required of automation professionals. You made the point about more than a dozen companies supporting a modern automation system in a typical production facility, which I find to be quite true, but I also include the number of different automation systems within the same plant complex for different processes, utilities and packaging to add to the number of workers and companies required. Most of those automation professionals don’t draw a paycheck from that manufacturer, but rather one of those multiple support companies you refer to in the supply chain.

Greg: How does the drive for cost reduction and flexibility in raw materials and products lead to more collaboration with automation system suppliers?

Steve: Quite simply, cost reduction, increased throughput, more consistent quality, safer environment, greater cybersecurity, and more should be drivers for control system migration away from legacy systems operating to yesterday’s production parameters. Whether the collaboration is with automation system suppliers, integrators or engineering companies, the market is driving the changes. Further, the more real-time we can get to the strategic decision process at the C level (e.g., chief executive officer, chief operator officer and chief financial officer), as Dr. Peter Martin has written extensively about, the more the company can control its own future.

Greg: We are fortunate in that there is not a manufacturing problem in terms of creating more jobs. How do we address the more evasive image problem?

Steve: That’s a good question. I’ve found that on Capitol Hill, even after years of advocacy, the political football that is automation is once again being portrayed as a “job killer.” While there are fewer line jobs than before, the crux of the multiplier effect is that the high-technology jobs required to support the modern plant exceed the lost line jobs by a multiplier. This number has changed according to who you engage in discussion, but it is still a large number multiplier. I believe that our profession is a victim of the identity shell game. Lawmaker staffs and others tend to identify industry by sector using a classification system developed by the government—Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) or North American Industry Classification (NAICS). As mentioned, the employees of the companies fit within the industrial sector, which is where the comparisons are made. The technology people working for companies in the supply chain are likely included in other sectors without relationship to the companies for which they do work. What should be perceived as an enabler for domestic manufacturers to be globally competitive seems to be cast by some as the boogieman to the middle class. This, combined with the lack of a clear automation engineering education path in academia, has pushed many bright young minds to other career pursuits. Perhaps the readers can now see the value in the automation competency model we discussed last issue as a beacon of what it takes to participate in this great career.

The multiplier and the consequential skills shortage is evident in the recent Deloitte paper, "Future of manufacturing: The jobs are here, but where are the people?" We in Automation Federation call on the Manufacturing Institute in DC. It is inside the greater National Association of Manufacturing (NAM). Blake Moret is the CEO at NAM. Blake was the CEO at Rockwell following Keith Nosbusch, who wrote the multiplier article about 10 years ago.

10. Do you like car speed control?

9. Do you like room temperature control?

8. Do you like hot water temperature control?

7. Do you like refrigerator and freezer temperature control?

6. Do you like smoke detectors?

5. Do you like carbon monoxide detectors?

4. Do you like traffic light control?

3. Do you like voltage control?

2. Do you like natural gas pressure control?

1. Do you like vehicle skid prevention and collision prevention?