By Steve Elwart, Ergon Refining, with Maurice Wilkins, and Steve Loranger

Strategic planning is enjoying a revival among many corporate executives, and rightfully so. However, when automation planning isn’t an integral part of corporate strategic planning activities, significant improvement opportunities and benefits can be completely overlooked and/or not fully realized.

Strategic planning shouldn’t be confused with long-range planning. Long-range planning assumes that current knowledge about future conditions is sufficiently reliable to ensure that a plan remains stable over the duration of its implementation. Strategic planning, on the other hand, assumes that the organization exists in a dynamic environment, where the ability to be agile and responsive is paramount to the company’s success. While a strategic automation plan should cover eight to 10 years, it must be reviewed and updated annually to accommodate business and technology dynamics.

The steps necessary to create a strategic automation plan are fairly straightforward. However, the tasks in each step aren’t easy or quick, and some of the tasks may be accomplished best by using outside resources.

Getting Started

Nearly every automation system installed for more than five years suffers from a patchwork of hardware additions and deletions, control strategy changes and miscellaneous integration solutions. Operators deal with alarms that are no longer appropriate and procedures that are out of date. Managers find it increasingly difficult to determine production performance during the previous 24 hours.

In such an environment, it’s safe to say that automation system investments are no longer optimized to help react to dynamic business conditions. The problem is that most companies don’t fully realize this until they establish a base case—a picture of where they are right now.

Not only does the base case frequently reveal some surprises—both positive and negative—but it also provides critical information that eventually helps answer the question, “What are the risks to our business if we do nothing?”

Developing a base-case picture requires dedicating a team to reviewing historical data, process flow diagrams, material balance calculations, operator logs and procedures, number and location of different data sources, how reports are created and used, and other activities appropriate to completing a “where we are right now” audit.

While it’s possible to use multiple interview teams, allowing the same team adequate time to conduct all the interviews often exposes weaknesses that might otherwise be overlooked, and it can provide a broader perspective of what needs to be addressed in the base case, as well as the strategic automation plan.

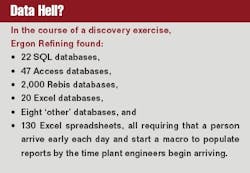

Discovery

Discovery is about setting aside preconceived notions. Discovery is about conducting investigations that reveal business improvement opportunities. Discovery is about asking a lot of open-ended questions and faithfully following where the answers lead.

It’s within the discovery process that outsiders (consultants or employees from another location) often produce more complete and often surprising findings than do insiders.

Insiders know the bumps and warts. They’re aware of the culture. They may even be part of a problem. So, expecting insiders to objectively complete interviews without injecting their own interpretations into the responses is expecting a lot.

One effective interview process involves using a seasoned interviewer and a rookie. The advantage of such an interview team is that the seasoned interviewer knows what questions to ask in order to kick-start a conversation, while the rookie, who may be unfamiliar with the industry and process will unknowingly ask clarification questions that often provide much-needed details.

For example, place a seasoned interviewer and a newbie in a break room with a handful of operators and technicians and start by asking, “What was the worst shift you ever had to work in this facility?”

Pretty quickly, the stories are flying, and people are interrupting with “Oh, it didn’t happen like that,” or “That’s nothing, let me tell you about…,” and then the rookie says, “I don’t understand. Tell me why that’s such a big deal?” That’s when the experienced operators and technicians transition into mentors, and begin diving into details that may eventually become gold.

When you resist injecting your own stories and listen closely, what you’ll take away from such interviews is a list of clues—possibilities you need to investigate until you have identified the root cause or determined that the clue is truly a myth.

It’s understandable why it’s important to determine the root cause, but it’s equally important to determine if “myths” are real or not.

Real myths are frequently the result of an occasional alignment of seemingly unrelated events. However, until actually proven to be a myth, you must assume there’s validity in the “nuggets” operators have been collecting over the years. Seek out the most senior people, and shake and sift those nuggets until either there’s nothing left or the “gold” is revealed.

Typically, discovery interviews begin as far up the organizational ladder as the interviewers can reach. It’s at these top echelons that information strategic to the overall success of the business is defined and discussed. But, it’s also important to check “low,” and validate with operations to ensure alignment from top to bottom. For example, one refinery was operating exceptionally well, and executives were taking a great deal of the credit. During interviews with operators, the consultant learned that the operators were running the plant completely differently than the executives had defined. In other words, it was the operators’ initiative that was contributing to the plant’s success.

Among the things executives and managers constantly attempt to balance is vision, mission, and values, often asking themselves, “Is it economical and in line with who we are as a company?” For example, “Are planned control room modifications in the operators’ best interest?”

By learning what the company truly values, what things executives and managers look at first each day, and by examining the value chain within the operation, you can eventually identify items that may be restricting growth or optimization.

While you may need to conduct periodic follow-up interviews, eventually you need to move from discovery, and begin processing the opportunities you discovered into quantifiable and measurable benefits.

Benefits

Without a doubt, quantifying benefits is the most difficult and subjective part of developing a strategic automation plan.

However, you’ll have an excellent starting point to determining benefits if you can interview the upper echelons of the company during discovery, and ask questions such as, “What would a 1% improvement in the area of incremental throughput be worth?”

If you weren’t able to obtain such information, then you need to seek assistance to determine incremental costs and values, and back-calculate reasonable numbers that help answer these questions.

Sometimes when the numbers aren’t available, improvements must be shown in other ways, such as throughput or product quality. This allows those working through the economics to establish realistic numbers.

Time is an often overstated, yet critical, aspect of defining project benefits. For example, if you’re conducting business in a highly dynamic environment, and you’re using a five-year return on investment capital (ROIC) time period for project justifications, you’re probably incorrect.

Think about how dynamic customer, product, supply chain and other business requirements have changed in the past five years. Isn’t it reasonable to assume similar dynamics are just as likely in the next five?

When preparing a strategic automation plan, it’s imperative that you know what ROIC periods your company is applying for various project types.

Developing benefits in isolation is just as risky as using the wrong ROIC time periods. To be credible, a strategic automation plan must illustrate how various aspects of your company compare to your direct competitors, your industry segment, and sometimes even outside your industry segment.

This is called benchmarking, and it’s not something to be trivialized. Be assured, your company executives are quite aware of how your company stacks up. In fact, it’s likely that their bonuses are linked to benchmarks.

Benchmarking

A common question is, “Where do I find benchmarking results?” The answer is, “They’re all around you.”

For example, we read about election exit polls, insurance coverage surveys, holiday shopping trends, etc. In the process industries, trade publications regularly report on job satisfaction (salaries and benefits) and the results of product and technology polls and surveys. For example, the Dec.’ 06 issue of Control included its “Top 50” list. Meanwhile, analysts and some consortium organizations conduct in-depth surveys, and develop detailed reports from the findings.

The point is: benchmark information is readily available, but you need to recognize it when you see it, and accept that it’s not always in a ready-to-use format.

Consider information that was published in a 2004 trade publication about stock turns, on-time, in-full delivery and cycle time, comparing companies within as well as outside the pharmaceutical industry. Is 2004 benchmark information still relevant? It’s likely the exact percentages will have changed since 2004, but probably only within the margin of error of the survey. Thus, this particular benchmark data remains relevant, but it’s always good to ask.

The important things to remember about benchmark data is that:

- You must determine the relevance of any and all benchmark data you’re considering.

- You must appropriately cite your sources.

Takeaways

The process of developing a strategic automation plan isn’t terribly complicated, and despite the number of different available models, each one uses similar techniques and yields similar results.

That said, accept that developing a strategic automation plan isn’t quick. For all the good things about having an excellent engineering and management team, this can actually work against you when trying to apply strategic thinking to develop an objective plan, especially when you try to develop it alone.

However, what seems to be the most difficult part of the entire strategic automation planning process is reporting, presenting, and following up.

Too often, the benefits and reporting are adequate to convince the person running the automation group and perhaps even good enough to convince that person’s boss, but it falls short of convincing executive management.

The Three Ps

Preparation and professionalism are paramount when selling to top management. Chief among the many pitfalls when presenting to executive management are a lack of awareness of other investment opportunities management is considering and presentation polish (professionalism).

Engineers need to be aware that their project is but one of many that executives are evaluating, and that each one is competing for a limited amount of corporate investment dollars. Anything less than a well-prepared, professional “sales” presentation—one that’s been rehearsed and critiqued and carefully designed for a specific audience—runs the risk of not receiving executive management approval. In Boy-Scout vernacular, “Be Prepared!”

Strategic automation planning is a disciplined effort to produce fundamental decisions and actions that shape and guide what an organization is, what it does, and why it does it, all while focusing on the future.

Being strategic means being clear about the objectives, being aware of the available resources, and incorporating both into being consciously responsive to a dynamic environment.

Automation is the only way to get your best operator, on his best day, every shift of every day. If that’s not strategic to a company’s overall success, we can’t imagine what would be.

Learn What You Don’t Know

A company with an established product and reputation insisted it simply needed assistance to develop an automation upgrade plan with a lengthy pay back period.

Encouraged by the consultant to work through the automation planning process, the company was shocked to learn that a competitor was building a new facility in a different area of the world, and that the facility would be online in two years producing product at a fraction of the cost.

As a result of the automation planning process, the company was able to change its investment plans, and was given a two-year head start on customer preservation.

| About the Authors |

Steve Elwart, PE, is director of systems engineering at Ergon Refining; Maurice Wilkins, Ph.D., is vice president of consulting at ARC Advisory Group; and Steve Loranger is vice president of business development at Emerson Process Management.

Leaders relevant to this article: