By Jim Montague, Executive Editor

Holding 8 or 10 ounces of boiling coffee in your cupped hands is tricky. Using a thick stoneware mug is easier, but you still have to be careful. Likewise, sturdy tools and finesse are needed to consolidate several control rooms into one, especially if you're going to more than triple production at the same time.

These were just two of the countless jobs facing engineers at BHP Billiton Worsley Alumina (www.bhpbilliton.com) when they and their many colleagues renovated and expanded their huge bauxite mine and alumina refinery a few years ago. Located near Collie in southwestern Australia, the company's operations presently refine about 3.5 million tonnes per year of bauxite ore into metallurgical alumina for later processing into aluminum. When the mine and refinery first started running in 1984, more than 50 operators managed production from five control rooms, and produced about 1 million tonnes annually. The initial control system was Honeywell Process Solutions' (hpsweb.honeywell.com) TDC 2000 analog distributed control system (DCS).

To carry out their overall Advanced Process Management (APM) project, BHP Billiton's managers and engineers agreed it should include the new central control room, advanced controls, alarm management and a partial control system upgrade to Honeywell's newer Experion DCS, operator stations, software and other equipment. The new controls also had to make room for and coordinate close to 4,000 process signals and more than 300 drives that were migrated from the old plant equipment to new systems, and do it without hindering operations.

However, elevating production performance in an alumina refinery is a challenge because it hinges on an operator's ability to be proactive and act on information appropriately. BHP Billiton's engineers realized that one catalyst to improving performance was to use advanced automation and user-centered design to replace some of the operators' current tasks, allowing them to focus more on production goals. "Following an extensive review of our process management, we knew we wanted to implement advanced applications and improve our production control," stated Angelo D'Agostino, BHP Billiton's senior process control engineer, in one of Honeywell's online success stories. "Our operators were key to this transformation and seen as the biggest lever to improve production and quality, and to decrease costs."

The project also was assisted by Ian Nimmo, then at Honeywell's Abnormal Situation Management (ASM) Consortium (www.asmconsortium.net), as well as system integrator I&E Systems (www.iesystems.com.au) and HMI specialist Acuité (www.acuite.com). However, though construction began in 2004 and the centralized controls have been up and running since September 2006, there were and remain some hurdles on the road to good user-centered design.

Confusion = Danger

In fact, most obstacles that hamper operators today are actually very old. And in many ways, process applications and their control systems still don't know how to get along with their data processing and computing counterparts.

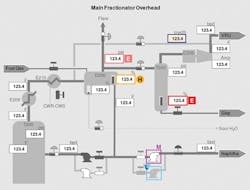

"Instrumentation designs were technology-centered for 50 years. Operators weren't considered when new methods were invented for showing what processes were doing, and so people became the bottleneck. Ever since computers began to be used on the plant floor in 1980s, the mistake was that controls and displays were made to look like P&ID drawings. But the problem with having many detailed P&ID screens with no hierarchy is that the operators can't distinguish what's going on where," says Nimmo, who is now president of User Centered Design Services (UCDS) Inc. (www.mycontrolroom.com). "These are not problems that ergonomics can solve. It's why we need user-centered design, so we can understand each operator's tasks, decide what information they really need to see, and provide the best information for them. We also need to make that information available in a useful hierarchy, instead of bombarding operators with the on-screen and alarm overloads. These come from bad design and can hinder instead of help operators because, if everything is red, then you can't discern what's important."

Figure 1

In March 2005, an explosion in an isomerization unit at BP Texas City killed 15 people and injured 170 others.

Waking Up from History

Fortunately, several other technical fields had operators in high-pressure situations who also were overwhelmed with data to the point of causing accidents, injuries and fatalities. For example, when airplane speeds increased during and after World War II, developers found that traditional control layouts weren't allowing pilots to respond fast enough to avoid crashing. Consequently, aerospace engineers examined what pilots must do to fly effectively, and in the 1970s began developing the field of situation awareness.

"Most of this work was done at Wright Patterson AFB and Wright State University, both in Ohio, and this is also how the field of human factors came about," says Dave Strobhar, PE, chief human factors engineer at the four-year-old Center for Operator Performance (COP, www.operatorperformance.org), which also is located at the university. "As the interest in operator performance issues such as alarms, HMIs, training and teams has grown, voids have been found in the available information. People estimate how many alarms they think operators can handle based on other industries, but most of these numbers are pretty arbitrary."

COP's members include BP, Chevron, Marathon Oil, Flint Hills Resources, Nova Chemical and Suncor Energy, as well as Emerson Process Management, ABB and is managed by Beville Engineering Inc. (www.beville.com). Though the center is relatively new, Strobhar reports its members' experience is extensive. In fact, in the past 25 years, Beville has performed 125 alarm rationalization projects for clients about how to respond to alarms, and reports that it can reduce alarms in most applications by 50%-75%.

"What we need is a free flow of information, so we can find out the best way to present data to operators and have academically defendable research about how to do it," says Strobhar. "We're also tackling topics like simulators, so when users are trying to decide between high- or low-fidelity simulators, they'll know the incremental performance benefits they can get based on how much more they're spending."

Implementing Awareness

To help users understand situation awareness and adopt user-centered design, ASM Consortium has made many of its recommendations and documents available to a wider audience. Peggy Hewitt, ASM Consortium's director and Honeywell's marketing director, reports that users can even order them at Amazon.com. "We have 15 years of research on best practices and the real science behind user-centered design principles," says Hewitt. "We have experience applying user-centered design when our customers apply our products, but we also consider it a core product development process."

Strobhar adds that COP has done several pilot studies on situation awareness and user-centered design issues, and found in its "Expertise of Process Control Operations" study that training and practicing decision-making skills can greatly help operators. Likewise, another study in 2007 showed that military-style decision-making exercises (DMEs) can be applied to process control settings, and some of these methods reportedly have been adopted by Flint Hills Resources.

Strobhar adds that COP also is working with Louisiana State University to study human response to simulated alarm rates, and is finding that the traditional view of performance degrading at one alarm per minute may be too conservative, and that two alarms per minute may be closer to where response begins to lag. Using these findings, they're also learning that better methods of presenting information to operators can improve their performance. "Traditionally, alarms are presented chronologically, and most operators still prefer it, but this is only better when alarms come in at a slow rate. When alarms are coming in quickly, we're finding that grouping alarms by priority allows operators to react and solve problems 40% faster. As a result, we're also going to study the best ways to switch between these two chronological and priority-group formats."

Figure 2

The ASM Consortium's "Guidelines for Effective Operator Display Design" recommends a simple, effective color scheme that can be used consistently and be easily remembered: gray and half-tones for piping and equipment; light blue is for low-priority alarms, orange yellow for high-priority alarms, and red for emergency-priority alarms.

ASM Consortium and Human Centered Solutions

Finally, after learning that shapes and colors in displays aren't as important as data content, Strobhar adds that COP is also examining how "cluster analysis" and more thoughtful and subtle color use can help present on-screen information so it makes more sense to operators. (Figure 2) "Critical information is often located on multiple screens, which requires users to scroll a lot, move from page to page, and remember earlier numbers too much, so we're study how to create a method to better organize this kind of information."

Though aircraft builders and military planners are further ahead on situation awareness, Nimmo agrees that process control developers are beginning to catch up. In fact, Nimmo adds that UCDS' three-day workshop can show users how to deploy better-performing graphics that can improve operators' process detection and diagnostics by 30%, and reduce response time by 50% in many applications.

Navigation, Procedures and Commitment

Similarly, Honeywell and the ASM Consortium have applied user-centered design in the areas of effective operator displays and alarm management for more than 10 years. Hewitt reports that the same principles are also being applied to how companies develop procedures in their organizations. "We've done a lot of research in the past couple of years on procedural operations, and trying to understand how console-based and field-based operators need to interact with their procedures," says Hewitt. "A lot of user-centered design is giving operators information when they need it." (Figure 3)

Figure 3

The ASM Consortium's "Guidelines for Effective Operator Display Design" also recommends shallow navigation (at right), in which all Level 2 displays are accessible from any location, and it takes only three mouse clicks to get from point A to point B.

ASM Consortium and Human Centered Solutions

In fact, ASM Consortium will publish its best-practice guidelines on procedural operations, Effective Procedure Management Practices, in June 2010. Liana Kiff, senior research scientist in Honeywell's Automation and Control Solutions (ACS) Laboratories, reports that many of the best practices for procedures are similar to those for displays and alarms, but there are some important differences. "We're finding that procedural operations are less about on-screen implementation and more about simply writing good process control procedures ahead of time," explains Kiff, who adds that procedural operations has been a core interest of the consortium since its inception. "This means asking what operators need to know to execute good procedures effectively and consistently. Traditionally, many procedures were written very loosely, and so 10 different operators at the same facility with the same task would each do it differently. To improve procedural consistency, management first needs to declare that it's important. Then, you have to get everyone to agree to the best method, train them consistently and then enforce compliance. Procedural documentation may range from guidance and training, to formal checklists and even to electronic solutions for tracking that specific actions are performed in sequence."

Teamwork + Proactive Ops = Better KPIs

Likewise, as with so many process control improvement projects, no gains can be made without genuine commitment from management. Besides securing this commitment, BHP Billiton's APM project and its control room consolidation also involved its operators from the very beginning. To create screens and displays that best fit their operational needs—a cornerstone of user-centered design—the team used Microsoft Visio software to design layouts and customized functions, and then inserted them into their Experion DCS using standard graphics-building tools. Once the new displays were built, the team trained other operators how to use them, and then organized five sub-teams to refine the displays into a simpler and easier-to-navigate hierarchy.

"Now we've adopted Abnormal Situation Management (ASM), trained our operators and left them alone to design their own screens, we've been pleasantly surprised at what they did," said Arnold Oliver, BHP Billiton's process control superintendent, at a recent Honeywell User Group meeting.

In fact, on one unit start-up, the team simplified its operator's job from having to do 24 navigation steps on 12 screens to using just one display. As a result, the operators found it takes much less time to do many typical tasks, that many jobs are easier and less stressful, and that they have more time and freedom to be more proactive. All this means better key performance indicators (KPIs) and better production. More recently, the refinery's user-centered controls also helped to expand its annual capacity again from 3.5 million to 4.6 million metric tons in 2008.

Yes sir, once you use that coffee cup, you'll never go back to cupping your hands.

How to Employ User-Centered Design

There are several main steps needed to successfully implement situation awareness and user-centered design in the interfaces, operator environments and procedures of most process control applications, explains Ian Nimmo, president of User-Centered Design Services Inc. (mycontrolroom.com). These steps include:

- Know your process application, the limits of your people and the information they need to do their tasks, and then account for all these factors consistently in how you design your interfaces, display screens, navigation steps, control rooms and operating methods.

- Don't deploy too many alerts or alarms; don't use excessive colors or graphics; don't set up too many display screens; and don't require too many steps to navigate between on-screen tasks.

- Use knowledge of your application and input from process operators to organize a hierarchy of graphics that permits quick drill downs to important instruments and measures. This should consist of an overview of all plants in the facility and offer a perspective on the most important alarms, so they'll show on what plant and where on it they're occurring. This hierarchy also should have a unit view showing specific areas or applications at each plant, a detailed view showing entire pieces of equipment and a diagnostic view showing the operating parameters for each device.

- Develop these new screens in accordance with how your plant operates now. For example, a facility with five plants should have an overview screen with what's most important at each, such as their furnaces or boilers. The second screen should have a unit view of each individual furnace or boiler, while the third has a detailed screen of its temperature, pressure, flow, level and other information.

- Reduce screens from the 12-16 typically in front of many operators to the four pre-prioritized screens recommended by the ISO 11064, Section 5, standard and the ISA SP101 draft standards.

Leaders relevant to this article: