Q: I’m working on a wind turbine control system and would like your advice on selecting the best wind direction sensor for yaw positioning and the best wind speed detection anemometer for turbine blade pitch control. I’m looking at mechanical anemometers and non-contacting sensors (ultrasonic, LiDAR, etc). I’d appreciate guidance on their relative performance and reliability, so I can base my optimization controls on their meaurements to maintain maximum tower efficiency.

Z. Friedman, control engineer / [email protected]

Get your subscription to Control's tri-weekly newsletter.

A1: In 1450, Italian architect Leon Battista Alberti invented the first mechanical anemometer. Today, designs include mechanical (vane, cup, propeller, turbine) units. They also include thermal, ultrasonic, pitot and laser-doppler types.

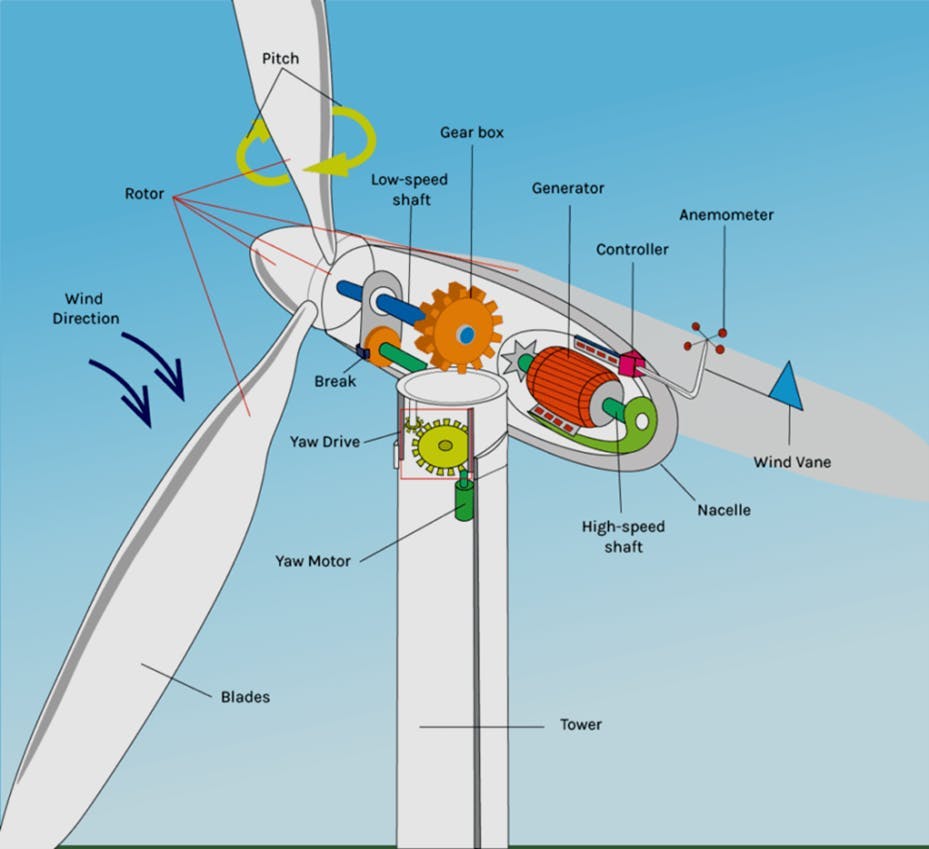

Mechanical anemometers: In this design, vanes rotate with an angular velocity proportional to wind speed. The three-cup anemometer is insensitive to wind direction. Usually, its shaft drives a direct current (DC) tachometer. These designs often include a wind direction sensor (Figure 1).

Impeller designs: These use a shaft-driven speed transducer and a tail, which always points the impellers into the wind. This type of instrument detects both wind speed and direction. The response speed of an anemometer is expressed in terms of the length of wind that must pass through the meter before the velocity sensor response amounts to 63% of a step change in velocity. This is known as the distance constant and is generally expressed in feet. A typical distance constant for commercially available units is 6 ft (1.8 m).

Thermal anemometers: These hot-wire anemometers operate as heated thermopiles that are cooled at a rate proportional to the air velocity passing by their probe tips.

Ultrasonic anemometers: Here, the time of flight of sonic pulses between pairs of transducers are measured. They’re suitable for exposed, automated wind-turbine applications, where the accuracy and reliability of traditional cup-and-vane anemometers are adversely affected by salty air or dust. One of their disadvantages is reduced accuracy caused by precipitation and temperature changes because they change the speed of sound.

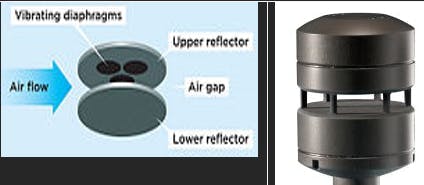

Acoustic resonance anemometers: These traditional, ultrasonic anemometers rely on time-of-flight measurement, while using ultrasonic waves in small cavities to perform their measurements (Figure 2). In their cavities are arrays of ultrasonic transducers, which create sound patterns at ultrasonic frequencies. As wind passes through these cavities, changes in wave property occurs, which the sensors use to provide accurate horizontal measurement of wind speed and direction.

Pitot tubes: These are differential-pressure devices with a pitot opening in the center of the tube (Figure 3) pointing into the direction of the wind. This total pressure port detects a higher pressure than the static pressure of the atmosphere, which is detected by the static ports on the sides of the outer tube. The difference between the two pressures indicates the wind velocity. Because of their low cost, these types of wind velocity sensors are popular, but they have low accuracy, low rangeability, and are limited to clean and ice-free applications, which wind turbines can seldom provide because plugging of the pitot opening can result in serious errors.

Laser doppler anemometers (LDA): When light is beamed into the atmosphere, dispersing particles reflect it, resulting in the doppler shift in the returning frequencies, which indicates wind velocity. That’s because particles under 5 microns move at the same velocity as air (Figure 4).

My answers are based on experience with indrustrial applications, but I have no direct experience with wind turbine applications. Therefore, I asked Dr. Eric Simley, a senior researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), to offer further informtion based on his much deeper knowledge of the field.

Béla Lipták / [email protected]

A2: The challenge with sensors that measure the wind on the nacelle (Figure 5) is they measure flow in the wake of the rotor and are disturbed by the presence of the nacelle. For wind speed, a nacelle transfer function is usually determined and applied to the measurements, so they better represent the undisturbed, freestream wind speed. However, there’s uncertainty in the nacelle transfer function correction.

One other issue I’ve observed with nacelle-based, wind-direction measurements is that, in addition to biases, they can overestimate the magnitude of the wind direction relative to the nacelle orientation. For some of our wake steering experiments, where wind turbines are intentionally misaligned with the wind to deflect their wakes away from downstream turbines, we’ve noticed that the nacelle wind vane measures a larger misalignment than measured by a nacelle LiDAR (e.g., 20° vs. 15°). So, the true achieved yaw misalignment appears to be lower than intended. I expect this only causes issues for wake steering. For standard yaw control, where the objective is to orient the nacelle into the wind, measuring the sign of the relative wind direction is more important than perfectly measuring the magnitude.

Because of uncertainties related to the nacelle transfer function, and because the wind measured at a single point on the nacelle might not represent the effective wind speed the entire rotor experiences due to wind shear or veer, nacelle-based, wind-speed measurements are only used for supervisory control purposes to determine when the wind speed is above cut-in or cut-out speeds. Model-based, wind-speed estimators are used for torque and blade-pitch control purposes. These estimators use an aerodynamic model of the rotor together with the measured generator speed, generator torque and blade pitch to estimate the rotor-effective wind speed. The use of wind speed estimators for wind turbine control is discussed in a paper that also provides an overview of wind turbine control in general.

Anemometers are traditionally only installed on top of the nacelle (Figure 5). Based on my experience, modern turbines from the past five years use sonic anemometers for nacelle wind speed and direction measurements. I believe they’re more accurate because they react faster to changes in wind speed or direction, and are probably more reliable, but I don’t have direct experience comparing the two technologies.

iSpin sensors: As an alternative to nacelle-based measurements, there is a sensor called the iSpin located on the spinner of the turbine upstream of the rotor. This avoids wake effects and other disturbances from the rotor and nacelle, but still measures the wind in the turbine’s induction zone, which is lower than the freestream wind speed, so a nacelle-transfer function would need to be applied. iSpin provides measurements of yaw misalignment as well as the vertical inflow angle, which could be useful for control. I’m not sure if this sensor has been used for control or if it’s only used for assessing wind-turbine performance.

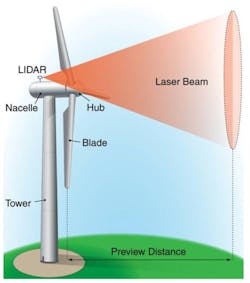

LiDAR sensors: If a light detection and ranging (LiDAR) system is used, it would also be installed on the nacelle and measure the wind remotely upstream of the turbine. Although less common, LiDAR sensors have been installed in the spinner of the turbine (i.e., the nose cone of the rotor), allowing measurements to be undisturbed by blade blockage.

Nacelle LiDAR has the advantage of measuring the incoming wind upstream of the rotor, where induction effects can be relatively low (the wind speed is close to the freestream wind speed). The preview provided by nacelle LiDAR measurements enables feedforward control strategies to reduce turbine loads from gusts and turbulence. Multi-beam LiDAR sensors can also provide a better measurement of the effective wind speed experienced by the entire rotor, as well as wind direction and shear measurements. One challenge with nacelle LiDAR sensors is they can only measure line-of-sight velocity, so assumptions about the wind field need to be made to estimate the different components of wind speed. For example, LiDAR typically can’t distinguish between horizontal shear (which could be caused by operating partially in the wake of an upstream turbine) and a non-zero wind direction relative to the rotor, so a wind field model assuming either perfect yaw alignment or no horizontal wind shear typically needs to be used to reconstruct the wind field. LiDAR measurements also might be unavailable if the aerosol density is too low in the atmosphere or if precipitation is too high. So, a controller that uses LiDAR measurements will need a backup option if it’s unavailable.

Blade pitch control: Wind sensors are usually not directly used in controlling blade pitch or generator torque, but only as part of the supervisory controller that determines when to start up or shut down the turbine.

Yaw control

For yaw control, there are control algorithms used to determine when to yaw the turbine. This is based on the amount of yaw misalignment measured. This way, the turbine doesn’t yaw too often. Although different turbines use different kinds of yaw control logic, they typically begin yawing when the accumulated or low pass filtered yaw error exceeds some deadband threshold. A deadband of around 8° is commonly used to prevent the turbine from yawing too much.

Wind turbines are traditionally controlled using only their own yaw measurements. However, recent research considered the yaw orientation of nearby turbines using a spatial average of the wind directions from neighboring turbines to create a smoother wind direction signal. In addition to improving power production, this type of control can reduce the amount of yawing (yaw travel) that the turbine experiences, improving the reliability of yaw drive components.

Rotational speed control: Generator torque is traditionally used to control the rotational speed of the turbine rotor (Figure 5), when the wind speed is below the rated wind speed (the wind speed at which the turbine’s maximum allowable or rated power is reached). At such times, the blade pitch is typically kept at its optimal angle to maximize power. Power electronics are used to create a specified load torque at the generator to either increase or reduce the speed of the rotor depending on whether the aerodynamic torque produced by the rotor is greater than or less than the generator torque. In these rated conditions, generator torque is used to track the optimal tip-speed ratio (ratio between the speed of the blade tips and the incoming wind) as the wind speed varies to maximize power production efficiency. Once the maximum allowable rotor speed is reached at higher wind speeds, generator torque typically regulates rotor speed at its rated value, until the wind speed increases to the point that the turbine generates its rated power. In this case, blade pitch control is used to regulate rotor speed.

Brake control: The brake is only used when the turbine shuts down or is parked. The blades will pitch to feather to slow the rotation of the rotor during a normal shutdown. The brake is used when there is an emergency shutdown.

Offshore cable control: Cable control is commonly used on both offshore and land-based wind turbines because, if the nacelle has yawed in the same direction too long, the cables running from the tower to the nacelle can require unwinding. The nacelle will then potentially yaw several revolutions in one direction to unwind the cables.

Dr. Eric Simley, senior wind energy control researcher, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) / [email protected]

About the Author

Béla Lipták

Columnist and Control Consultant

Béla Lipták is an automation and safety consultant and editor of the Instrument and Automation Engineers’ Handbook (IAEH).