Slow and steady is fine. Fast and steady is better.

Because it's progressing far more quickly than typical standards efforts, the Open Process Automation Forum (OPAF) is quickly ticking off milestones on its march toward interoperable, plug-and-play process automation and control. The latest developments include:

- Finalized and released Open Process Automation Standard (O-PAS), Version 1.0 (V1.0) on interoperability, in January at the Open Group's meeting in San Antonio, less than a year after releasing its preliminary version. It's five parts—technical architecture overview, security with IEC 62443, function profiles, open connectivity framework (OCF) interfaces, and system management—focused on meeting the minimum standard and specification requirements for federated process automation systems, using an open and interoperable reference architecture.

- Released preliminary O-PAS, V2.0 on portable configuration of distributed control systems, on Feb. 4, during the ARC Advisory Group's Industry Forum in Orlando. OPAF's technical committee has been working on V2.0 for the past year, and plans to release V2.1 on portable application configuration in mid-2020.

- Published the O-PAS Conformance Certification Policy on Feb. 4, which defines for suppliers what can be certified, what it means to be certified, and the process for achieving and maintaining certification. It also defines supplier obligations, such as requiring them to warrant and represent that their products meet applicable conformance requirements, including conforming to O-PAS as interpreted by OPAF. In conjunction with applicable conformance requirements, certification agreement and trademark license agreement, this policy constitutes the set of requirements and obligations for achieving certification.

Plug-and-play progress

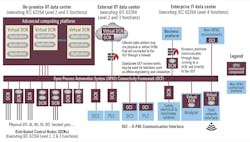

Even though O-PAS is designed to be a standard of standards that integrates other industry best practices, each piece of OPAF's vision for it is intended to provide the interoperability needed to streamline process automation and control projects and operations on plant floors and in the field. Its architecture describes distributed control nodes (DCN) and virtual DCNs for working with physical devices, an OCF such as OPC UA for networking, and an advanced computing platform (ACP) for higher-level data processing, but these generic terms and the progress at each stage of the O-PAS effort are all focused on giving users plug-and-play components and software (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Open Process Automation Forum's (OPAF) interoperable Open Process Automation Standard (O-PAS) networks production-level distributed control nodes (DCN) via a real-time bus/open connectivity framework (OCF) such as OPC US to manufacturing OT data centers using a real-time, advanced computing platform (ACP), enterprise IT data centers using business platforms, and external data centers using cloud-computing services. Source: OPAF

"We have a broad set of assets and sites worldwide, as well as up to 30-year-old systems and staffers who have been with them all along, and are now retiring. An even bigger challenge is cost constraints and how to be cost-effective, so we're defining a point in time to achieve more open and interoperable systems," says Jacco Opmeer, DCS subject matter expert at Shell, and co-chair of OPAF's Business Working Group. "This can be called lifecycle management, but it's also prioritizing the parts we need to work on, and supporting critical processes with hybrid responses, some done by us and some by main automation contractors (MAC) and other suppliers. At present, lacking openness and interoperability means we often can't use best-in-class solutions, and must use what we can get from certain suppliers. We believe O-PAS will enable us to access more and better tools, open up new capabilities, and give us some huge benefits thanks to interoperability. Another challenge is stabilizing operations at multiple sites, but openness and interoperability can enable many solutions here, too. If more users can be convinced to join OPAF, they can think up their own use cases."

Power of portability

Of course, now that O-PAS V1.0 on interoperability is final, its five parts are being used to prepare for O-PAS V2.0 on configuration portability.

"Version 2.0 gives us the pieces for an open distributed control system (ODCS) specification that allows portable configuration of DCSs. Vendors can support configurations, and generate downloads for their O-PAS implementation," says Dennis Brandl, principal consultant at BR&L Consulting Inc., co-chair of OPAF's Technical Working Group, and chair of its Technical Architecture Subcommittee. "These specifications are based on Automation Markup Language (ML) and its IEC 62714 equivalent, which is an XML-based, common data format and design-time tool. In this case, it includes the information needed to configure an ODCS, such as what signals come into the system, what leaves the system, the alarms and controls. Vendors will use the O-PAS specifications to develop or extend their configuration tools and control products."

Brandl reports that AutomationML files in O-PAS V2.1 will also include the source code for their programming. "These are the basic parts required to program using IEC 61131-3 for PLCs and IEC 61499 for function blocks. The O-PAS specifications include rules about where to put all of the files needed for a configuration, so users can capture the whole configuration of a system in a single, common AutomationML file. All of the development work on the O-PAS specifications is moving forward rapidly, and there are many vendors working on products. They've seen how static the DCS market has been, and they want to shake it up."

Brandl adds that configuration portability in V.2.0/2.1 will lead to OPAF releasing O-PAS V3.0 supporting application portability in 2021. "V3.0 will let users take applications united by their standard control languages, and distribute them across devices from multiple vendors. This is the holy grail of interoperability that we've all been pursuing," says Brandl. "At the same time, we'll also be setting up testing and certification labs by the end of this year, which will join the non-plugfest events we're holding."

Streamlining for skids

As progress on O-PAS and its many subsections continue to bring it closer to reality, its developers and supporters are detailing how the standard can enable process applications, such as increasingly modular manufacturing installations.

"We've been working on open process automation for eight years, and more recently talking about proof of concepts and prototypes, but the exciting news is we're way past the idea stage. This is no longer a dream or vaporware. Our job is identifying interoperable, interchangeable, portable, plug-and-play technologies that can solve problems for users, and O-PAS is opening those compatibilities, and will allow their businesses to create value," says David DeBari, process control engineer at ExxonMobil Research and Engineering and lead engineer in its OPA program. "We're still asked why not just use a traditional DCS, and the answer is their high costs and 20-30 years between product refreshes. They often don't allow different devices to talk to each other, so we can't use best-in-class products. We also need cybersecurity that's built-in from the ground up because we can't keep bolting it onto DCSs that didn't have it before and patching existing processes."

Julie Smith, global automation and process control leader in DuPont's Engineering Technology Center, adds that O-PAS is valuable because it goes down to Level 2 supervisory control and Level 1 basic control of the seven-layer Purdue Open System Interconnect (OSI) model for system and control hierarchies. This is where O-PAS application portability can break through the proprietary devices and systems that have long dominated those layers.

"O-PAS enables the integration of skids, which is how we're growing our specialty chemicals business lately. We're not building new plants as much as we're mostly adding processing capabilities with skids, but it's been difficult because there's no one standard that enables us to integrate them," explains Smith. "We're already supporting all kinds of process controls and automation systems, usually with self-support at our large sites, some support contracts and local system integrators at our small sites. However, our recent merger and acquisition activity is making these challenges more acute, which makes it even more crucial that O-PAS can solve these pain points for us."

As shifting corporate strategies and markets increase pressures to reduce costs, Smith adds that O-PAS can go beyond supporting existing operations to also enable migration and upgrade efforts. "There's no one-size-fits-all when it comes to operations supporting production, and O-PAS doesn't change that. However, we only do migrations when we have to because there's typically no financial return on them," says Smith. "O-PAS can make it easier to do those projects by enabling 'upgrade by repair' versus rip and replace. This will allow us to incrementally take advantage of new technology as it becomes available.

"Four years ago, there was a lot of disbelief about O-PAS, but seeing the OPA prototype shows that it's really going to happen. We may not be able to buy its components yet, but we will soon, so why shouldn't we have a voice in how they're shaped and developed? For end users wondering why they should join OPAF, the questions are: 'Why let others decide?' and 'Why not be part of shaping O-PAS, so it will benefit me?' No one really wants a finished standard to just drop in their lap."

Smith reports that OPAF will be holding requirements workshops in 2020 where smaller companies can contribute. Plus, they can also ask their suppliers if they're aware of O-PAS and/or planning to join OPAF. "There's a growing recognition that the world and supplier environment is changing, and that we can all enable new opportunities and grow the process control and automation pie," adds Smith. "I want application portability because if I have great strategy and a software app from one vendor, then I may want to be able to run it on another vendor's hardware."

Prototype and pilot progress

Making equally rapid gains, OPAF founding members ExxonMobil, initial system integrator Lockheed Martin, and their collaboration partners have been forging ahead with their OPA program. It also added vendor-independent system integrator Wood, and has progressed from an initial proof of concept (PoC) for a simulated fired-heater to a larger prototype that achieved interoperability and portability on a pilot plant at its research facility in Clifton, N.J.

The prototype/pilot unit includes four reactor trains with pumps, reactors, separators and analyzers managed by 25 typical process control loops, 130 I/O devices and 500 total points. The hydrocarbon service process includes crude oil and hydrogen feeds, and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) presence that runs at an 8 gm/hr liquid feed rate, 600 °F, and 1,200 psig, and is used to evaluate catalyst performance. The prototype/pilot completed its site acceptance test in January 2020, and DeBari reports it's been performing normal unit operations using its OPA system, such as startups and shutdowns, controlling unit parameters, and meeting operator expectations.

The prototype/pilot captures data using OSIsoft's PI Historian software and Inductive Automation's HMI/SCADA software, and its architecture also includes hardware and software from Dell, nxtControls, Phoenix Contact, Intel, Yokogawa, Moxa, Lantronix and Matrikon. Its DCNs include a catalog controller from Phoenix Contact, VM-based soft controllers, a custom, two-piece DCN concept from Intel with four channels, and a swappable, cassette-style microprocessor assembly for switching compute functionalities. They communicate via OPC UA on a real-time bus divided into six cyber-secure zones with soft controllers and other functions in a Dell VxRail ACP server (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The open-process automation (OPA) pilot plant developed by ExxonMobil and system integrator Wood includes four reactor trains, 25 control loops, 130 I/O and 500 points in a hydrocarbon service running at 600 °F and 1,200 psig, and is based on their prototype OPA system architecture with distributed control nodes (DCN) communicating via OPC UA real-time bus with soft controls, HMIs, alarms, historians and other functions in a Dell Vx Rails advanced computing platform (ACP). Source: ExxonMobil

"We have a lead operator, who will provide a real-time performance appraisal of the prototype/pilot, and if she's happy, then we're happy," says DeBari. "At the factory acceptance test (FAT), it only took her seven minutes to find something she didn't like, which was a missing data value on a screen, and then it only took her 23 minutes to try a process operation using the system that we hadn't heard of or added before. This is why having an operator driving is the most rigorous test that a new process control system can face."

Test bed takeover

Once the prototype/pilot unit runs for several months and demonstrates the technical feasibility of its open-process components, its results will inform the test bed to evaluate OPA components and methods in 2020-21, which will support industry field trials to demonstrate OPA technical readiness in 2021-22. The test bed will consist of a virtual separation tower with hardwired I/O and simulated signals at ExxonMobil's facility in The Woodlands, Texas. The model will also gauge suppliers' capabilities for producing O-PAS-aligned components. Possible experiments that may be conducted using the test bed include:

- Batch and sequence control;

- Containers and orchestration;

- Root of trust and certificate-based security;

- Clock synchronization among devices, such as time vs. event-based;

- Added DCNs from new suppliers;

- Wireless instruments;

- Mobility enablement, such as HMI on a tablet PC;

- Third-party applications, including app store feasibility;

- Network security options, including virtual local area networks (VLAN), firewalls and zones/conduits;

- Publish/subscribe network testing; and,

- Network design and protocol performance testing.

To help coordinate test bed participants, Yokogawa Corp. of America has been enlisted as the system integrator, and operates the test bed facility. Results from the test bed will create a foundation for the field trials that will be carried out by ExxonMobil and its partners, including Aramco Services Co., BASF, ConocoPhillips, Dow, Georgia Pacific, Linde and Reliance Industries Ltd. Beyond agreeing on the need for OPA systems and their desire to accelerate development using multiple, parallel field trials, these partners will: pick their own system integrators; use O-PAS as available; share non-competitive learnings with each other; and develop additional test bed experiments.

"Beyond adding and testing devices, one of the test bed's most important tasks is to help participants understand the O-PAS system architecture and how it all fits together," explains DeBari. "Once all the partners learn how to use O-PAS-based process control, then we'll be able go our separate ways to implement them in our individual applications. Test bed experiments for functions like batch will require some more equipment, and the tests will help identify components and help developers create apps for end users, who can then pick the ones they need for their processes. We still need a critical mass of users and a supply of compelling software and hardware for O-PAS to succeed."

Stephen Smith, control systems support manager, Eastman Chemical Co., reported at the ARC event that his company joined OPAF in late January, and is intrigued by its potential to achieve interoperability, even though some questions remain. "We joined about a week ago, and we're excited about the value that OPAF may be able to provide, but some in our organization are skeptical that it will really happen and come to fruition," says Smith. "It was fairly easy to join, and we signed up for one year as a 'trial,' but if we decide it's not useful, then we can leave. For now, I think it helps to be at the table, and see what OPAF is doing and what's coming."

Enlisting everyone

Beyond recruiting more potential users, DeBari adds that software programmers, system integrators and suppliers are needed to further develop and test O-PAS and its capabilities.

"Our original vision for interoperability and O-PAS was based on a system we had to put together ourselves. We wanted our devices to plug-and-play like regular stereo equipment, printers and PCs, but they need to be based on models and methods that all participants must agree on. Our goal is not to run any suppliers out of business because we continue to need them as partners, too. Plus, we also need to allow in other suppliers that may have been locked out in the past due to proprietary issues. So, we need all suppliers to maintain their support, and also help us integrate with existing systems.

"When we talked to system integrators about our OPA program, we were reminded they often buy process control solutions from third parties, but we can't just do that anymore. Marketplace competition means we all have to understand the OPA Business Guide developed by OPAF's Business Working Group, which lays out the ways for everyone to participate. In general, we're not putting as much steel on the ground as we used to, and we're also not throwing away old equipment, even though we're moving to gain new capabilities. We believe O-PAS is an excellent vehicle for achieving these new benefits. This is what our C-suite wants, and if they don't get these capabilities with O-PAS, then they're going to get them another way.

"The interoperable, interchangeable, portable, plug-and-play future we've talked about for a couple of years is now the present that we're living in, and we can't thank the vendors enough for supporting, participating and adopting openness. There's no 'if' about O-PAS anymore. It's all 'when' and that when is coming soon. Our PoC was all customized, and so the prototype's goal was to minimize customization and use available equipment, such as the Phoenix Contact and Yokogawa components that can be bought right now. We aren't seeking technology that hasn't been done before. We're seeking the equivalent of plugging in printers without having to set up a software driver, and a cell phone-style marketplace for devices in the plant that we can buy, and use the software we need from an app store without proprietary restrictions."