This article was printed in CONTROL's June 2009 edition.

By Nancy Bartels

Shakespeare, always a man able to nail a situation with a few well-chosen words, called it "the winter of our discontent," which is a pretty good way to describe the feelings of the more than 1,500 respondents to our 2009 salary survey. No matter that the actual key numbers shown have changed little from last year in most categories. Except for a few sunny optimists and contented souls, most of those surveyed are Not Happy.

Much of the discontent is an understandable free-floating anxiety about the economy in general and job security in particular. Some of it relates to perennial complaints about the "suits" that "just don't get it;" the clueless newbies who seem to be less well-prepared to enter the workplace than ever; the parsimonious bean-counters who are penny-wise and dollar-foolish; and the sense that the people who do the real engineering work don't get the respect they deserve. Some unhappiness reflects the frustration that comes from dealing with long-ignored issues, such as the aging workforce and related loss of intellectual capital to retirement, continued outsourcing of work to lower-cost countries, the persistent demand to do more work with fewer people, and long hours and lack of concern about work-life balance.

Whatever the reasons, this winter seems a particularly cold one. Interestingly, the statistic in our survey that has changed the most is "number of respondents." Last year about 750 engineers took time to fill out the survey. This year, the number was more than double at 1,594. Three hundred and forty five of those took the time to add additional comments to their surveys—and it is in those additional comments that the icy winds are felt.

One Texas-based chemical engineer summed things up succinctly: "I don't get to see my family when I work 70 hours a week. This job sucks."

A Louisiana-based process engineer with a master's degree added, "We have a transient workforce. Corporations are treating their workers more and more like temps."

An Ohio-based chemical engineer who has worked at the same company for more than 20 years says, "Recognition and advancement opportunities are generally only for those in management. Those doing the work to produce a quality, cost-effective product are treated as a necessary evil."

And an Illinois-based electrical engineer chimes in about management: "They do not have a clue as to what we do, how we do it, or what landmines lay ahead." This is happening despite the Automation Federation and ISA's work with the U.S. Department of Labor on raising the identity of automation professionals.

By the Numbers

Oddly, at first glance, the numbers in our survey don't seem to warrant this gloom. Most of the 2009 numbers are within two to three percentage points of last year's results.

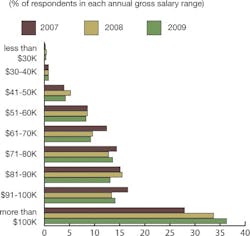

Comparatively speaking, process automation folks make good money. This year, 50% of our respondents make more than $60,000 and 36% make more than $100,000 per year. That's up from only 28% in 2007 (Figure 1).

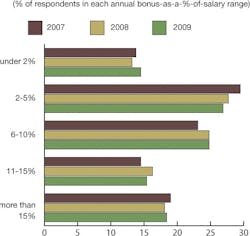

Raises remained good across the board. Ninety percent of our respondents reported getting a raise last year—54% of them between $2,000 and $4,000 dollars. A substantial 16% reported raises between $5,000 and $7,000. A lucky 5% reported raises of $8,000 to $10,000. In addition, 68% of those surveyed reported getting a bonus last year. A little more than a quarter of them (27%) fell in the 2% to 5% range, and another quarter in the 6% to 10% category, but a substantial 18% reported a bonus of more than 18% of their salary. These numbers nearly match those in the 2008 survey (Figure 2). Of course, many of those bonuses may have been earned before the shoe dropped at the end of 2008. It will be interesting to see what the bonus numbers look like in next year's survey.

Figure 2. Bonus dollars came to 68% of those surveyed. The bonus as a percent of salary ranges remain close to last year's numbers.

Benefits remain fairly typical, with 98% reporting they get medical coverage and 89% reporting that they get dental insurance. Eight-eight percent have company-paid life insurance and 77% get disability. On the other hand, pensions continue to decline. Only 48% of those surveyed reported getting a pension, down from 54% in 2006, but 90% say they have a 401K plan, and 15% say they get stock options—which, given current stock market conditions, may put something of a damper on those big gross salary numbers. Notably, 30% now say they get flex time and 9% have the option of telecommuting—perhaps because of company dollars spent on wireless connectivity and Internet-enabled resources.

Vacation time numbers shifted only marginally. In 2008, 32% reported having three weeks' vacation. This year, it was down to 30%. But those taking four weeks moved up slightly from 26.4% to 27%. Those taking more than a month increased from 27% to 28%—a number probably reflective of the advancing age and seniority of many of our respondents.

The downside of this apparent largesse is that it comes at an increase in the number of hours worked. As in 2008, nearly 78% of respondents said they worked 41 to 60 hours a week—a number that has remained remarkably steady in our survey since 2005. Another 10% said they worked more than 60 hours. And nearly 79% reported they didn't get paid for overtime, up from 77.2% in last year's survey.

However, buried in these seemingly nearly static benefit numbers is one of the sources of discontent. A Michigan-based plant maintenance technician reports, "The company just got rid of its pension plan and announced no raises this year, except medical costs went up."

An Indiana-based mechanical engineer in plant operations and maintenance for a plastics plant added, "Employee contributions for medical benefits keeps eating up any raise that is received. Deductibles for medical are very high and result in another $200-$300 dollars a month in expenses to cover the deductibles and out-of-pocket costs. The net effect seems to be a reduction in the overall compensation."

"We are seeing a decrease in our benefit package. Larger medical insurance contributions by staff, larger co-pays and decline in coverage," adds a water and wastewater operations technician from Michigan.

In short, says a plant maintenance engineer with more than 20 years experience in the plastics and chemical industries, "Salary is not keeping pace with benefit decreases."

Figure 3. The profile of the typical process automation engineer has changed little over time.Perhaps here is the place to note that, despite good wages and benefits (well, maybe not as good as they were, but still better than in many other industries), most engineers aren't in it for the money. Nearly 44% said the most important contributor to their job satisfaction was having challenging work, compared to 16% who said it was the salary and benefits, a number that comes in third after "appreciation" at 17%. Another 14% say the most important thing to them is job security (Figure 4).

High Anxiety

Yet job security is the source of a lot of the anxiety, frustration and anger in our survey. The current economic situation leaves our respondents more than a little nervous about their jobs—and who can blame them?

Fifty-two percent of those we surveyed said they were concerned about job security, which is not a bad number, considering the current state of the economy, but down significantly from the 58% who said they weren't concerned last year. This drop is one of the deepest in all the categories in the survey.

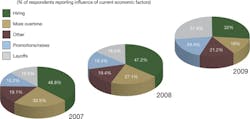

Interestingly, the number of people saying their companies are hiring or conducting layoffs is almost equal—38.2% and 37.9%, respectively. Nearly 25% say that raises and promotions were affected by the economy, up from 19.4% last year (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Companies hiring and laying off are just about even.

However, those nearly even hiring/layoff numbers don't mean that our survey respondents aren't worried about their jobs. Says a Texas-based technology department manager, "The current operational atmosphere is similar to living in a downstairs apartment: You're always waiting for the next shoe to fall."

Mike Dionne, design manager with Integrity Integration Resources, Plano, Texas. says, "The market has really slowed down compared to the past several years. We are holding our own with just enough work to keep busy,"

A Virginia-based engineer with a master's degree in chemical engineering and 20+ years' experience in the chemical industry adds, "Lack of job security is still a threat. Salary increases are falling below inflation."

For David Calo, chief engineer for a large New Jersey-based food processing operation, the outlook is bleak. "Most likely to be outsourced this year," he predicts. (Control checked back with Calo, who reported that his prediction had been correct. The outside company hired members of his department to fill positions, but also reorganized it and eliminated some jobs.)

For the employee of an independent engineering firm in Ohio with more than 30 years experience, the situation is even bleaker. "Presently on temporary unpaid furlough, although I am provided with benefits," he reports.

And, of course, for those left behind, there is the inevitable doubling up of responsibilities and some unintended consequences. As a Virginia-based mechanical engineer working in plant maintenance for a chemical company explains, "The current demand for experienced engineers has kept layoffs in check, but the do-more-with-less philosophy due to the current economic situation is affecting quality."

The Outsourcing Villain

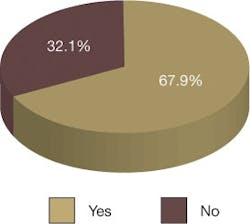

With all this job anxiety at home, the subject of outsourcing, always something of a sore point with our respondents, remains one, although the outsourcing numbers have not shifted significantly from last year in spite of the economic downturn. Nearly 68% of those surveyed said their companies outsourced professional or engineering services, down only about 1% from last year. Forty-eight percent of those surveyed said their companies' outsourcing levels were about the same as last year. Nearly 32% said their companies were doing less outsourcing and only 20% said they were doing more (Figure 6).

Figure 6. About the same number of companies overall are outsourcing, but the number doing more than last year has dropped 12%.

But again, the static numbers don't reflect that fact that the subject hits a nerve with our respondents. Jeffrey Bartman, a systems engineer with Proconex, Royersford, Pa., a control products and services distributor, puts a finger on the fear running through the comments. "Engineering is becoming a victim of outsourcing to India and China," he says.

A Missouri-based electrical engineer working for a chemical company amplifies the grievance. "Not only have we been offshoring our engineering work to India, we have been bringing resources into the United States on 18-month visas to perform the work here. My company says this is because we cannot hire enough qualified people. The real problem is that they are not willing to spend the effort and money to train them."

A quality control engineer for a pharmaceutical company in Maryland adds, "Whenever I hear a ‘suit' say, ‘Our employees are our greatest asset,' what I hear is ‘These damn employees are obviously our greatest liability (drain on profits), and let's see if we can do it cheaper in China, India, Pakistan.'"

So, is every thing in process automation horrible? Are people hanging on to their jobs only because there's nothing better on offer? Well, that may be the case with some, but in spite of the very real angst among our survey community, only one person said he doubted he would recommend that his children follow in his steps on the process automation career path.

The praise may be a bit more muted than in times past, but some, such as production control specialist Bill Dunmead of food distributor Novamex, El Paso, Texas, still says, "I am happy where I work."

Brent Beebe, operations manager at meat processor Agriprocessors, Postville, Iowa, chimes in: "This is a good place to work."

Dennis Christiansen, a senior sales engineer at United Electric Supply, New Castle, Del., says, "My workplace and the people I work with and for are very good and have been for most of my career," although he qualified that by adding, "The recent layoffs were hard to accept, but necessary. This is going to be a tough market for awhile, at least well into next year."

In spite of all the anxiety and genuine anger over the real or perceived current state of affairs, some folks find process automation a good place to be—or think it will be again once the economy straightens out.

Nancy Bartels is Control's managing editor.

Leaders relevant to this article: