If you took a shower this morning, you probably didn’t immediately jump into the water. It might have been intuitive to turn on hot and cold water, jump into cold water, open hot water more, continue to be cold, continue opening hot water until it got warmer, open it a bit more to make it comfortable, recognize that it is now hot, then scalding, then frantically turn down hot water until after much pain and frustration you can endure a shower. The consequences for an industrial process can be far worse than temporary discomfort. A control loop that behaves this way can result in disastrous economic loss, equipment damage and injury and/or fatality.

Most of us know from experience that when we take a shower we need to wait while we sense the temperature with our hand and adjust the valves to produce the right temperature before we hop in. However, many industrial control loops have been implemented without recognition of deadtime.

Get your subscription to Control's tri-weekly newsletter.

Defining deadtime

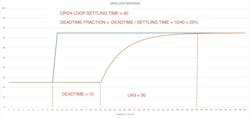

Deadtime is the term used to represent process delay. The time between movement of an actuator (controller output) to movement of the measurement (controller process value, PV) is deadtime. An open loop response with deadtime is shown in Figure 1.

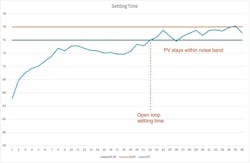

The open loop settling time is not always easy to determine. Since all processes have noise, there is no guarantee the PV will ever settle. The ISA 5.9 technical report defines closed loop settling time as the time at which the PV stays within a percentage of the setpoint. Open loop settling time is determined as the time the PV is persistently within the noise band of its final value, as shown in Figure 2.

If deadtime accounts for more than 20% of the open loop settling time, a PID loop (no matter how it is tuned) may be unstable. It is impossible to tune a PID loop if deadtime is too significant. Unless deadtime is reduced (through process design or mechanical means) or accounted for in the control algorithm, no setting of PID will prevent unstable responses, meaning the loop in “AUTO” mode has persistent oscillation from maximum to minimum output (very dangerous) or a loop that is always in “MAN” mode. Many loops in industry are locked in manual mode for this reason.

Case Study: Plummer Forest Products

On March 24, 2019, a fire at Plummer Forest Products in Post Falls, Idaho, destroyed a considerable portion of the facility. Plummer had contracts left at risk if it could not quickly restore production.

Plummer produces wood boards from sawdust and scraps from lumber mills. The boards are used for flooring material and have precise weight specifications.

Included in the destruction was its control system, a combination of SCADA that implemented discrete logic with a proprietary system that measured the weight of the boards and performed all analog (regulatory and advanced) control. Restoring production required automatic control of board weight to the same previous standards.

While the SCADA system could be upgraded with the ladder logic reprogrammed in the new platform, the analog control either needed to be restored in a proprietary system or translated into the new SCADA platform. Plummer chose to implement these controls natively in the new SCADA system.

The most complex control problem in this system is control of the board weight. The process illustration shows wood from the inside silo metered with a variable speed screw feeder to a fixed speed weigh belt, which then feeds wood into a blender with chemical addition. The blend is moved by a conveyor into a chute with a splitter gate to proportion material between the upstream and downstream side of a forming bin. Having an upstream and downstream side of the bin ensures an even spread of material to form a uniform wood board. Each side of the forming bin has a variable speed belt with load cells under them to determine the level of material on each side. The belt speeds are synchronized to spread the material evenly on the forming line that transports the material to the mat scanner that will measure its weight. The weight measurement will be used to adjust the belt speeds. The mat scanner is a scanning sensor with a nuclear source producing a board weight measurement approximately every 15 seconds (Figure 3).

Breaking this down, there are three coupled (interacting) loops involved in control of board weight:

- The bin level is the average of the two load cells under each of the forming belts. The bin level is maintained by the variable speed screw feeder, which is quite a distance upstream of the bin. The production rate is not constant for this process (wood addition rate can be 319 lb/min to 733 lb/min), but typical deadtime between the bin level measurement to the screw feeder is 40 seconds and the lag is 20 seconds, meaning that since deadtime far exceeds to settling time, it is a deadtime dominant process. Since this is level control, it is an integrating (not self-regulating) loop.

- The splitter gate must maintain the ratio of bin level between the front and back of the bin. The setpoint is normally 50% (equal level in each side of the bin). This is a very sensitive loop that is also integrating. The deadtime for this loop is negligible, but if the splitter gate is not in the right position, the level ratio can quickly get out of whack, requiring special, tight tuning to respond quickly but remain stable.

- Finally, the weight of the board must be controlled to its quality level. Different grades of board have different setpoints for board weight. Because the quality of wood can vary, unmeasured disturbances can result in board weight deviations without feedback control. Therefore, closed-loop control of board weight is a critical component of product quality. As previously mentioned, production rates are not constant but the typical deadtime from the mat scanner to the front and back variable speed bin belts is 30 seconds and the lag is 40 seconds. It is also a loop with more than 20% of the settling time composed of deadtime. This is a self-regulating loop.

It is impossible to implement a successful control strategy for this application with PID alone.

Implementation

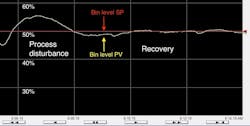

Bin level control was implemented with deadtime-compensation logic natively in the SCADA system. No additional software license was required. Due to variable production rate, a feedforward algorithm was implemented to reduce disturbances due to changing rates. To the operator, the bin level has the same appearance as any PID loop. Figure 4 shows the bin level control recovering from a process disturbance to maintain tight level control at the 50% setpoint.

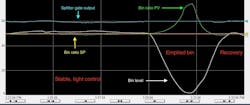

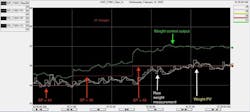

The former bin level and splitter gate logic required on startup (when the bin was empty) so the level ratio could be controlled as the process started up. It presented a challenge since the head ratio measurement is sensitive when the level in the heads is low. A bypassable interlock was implemented to put the loop in manual when level is below 30, allowing the splitter gate to be positioned in a stable way as the bins filled, and then return to auto control when the bin ratio measurement was more stable. In auto mode the PID require tuning of the derivative term to provide the stability and tightness required. In Figure 5, control is tight and stable prior to the bin being emptied. When the bin is emptied, the bin ratio measurement gets skewed even though the splitter gate has been locked in place at 60%. After the process is restarted and the bin level begins filling, the control recovers very well and returns the ratio to setpoint.

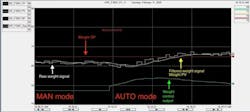

The weight control was implemented in a very similar way to the bin level. A filtered signal was derived from the raw sampled mat scanner weight to provide a continuous PV signal that removed noise. Again, the deadtime compensation was implemented natively without requiring an additional software license, and variable dynamics were considered through a feedforward signal. In the trend shown in Figure 6, the raw measurement and the resulting filtered weight measurement that is the PV of the loop. When the loop transitions from MAN to AUTO mode, the loop responds well and maintains weight to the SP.

Current condition

The control strategy with final tuning and configuration has been in place since February 2020. Because the strategy was implemented using native SCADA capabilities, the facility has been able to maintain configuration and implement modifications such as additional interlocks and logic. The loops have nearly 100% utilization in AUTO mode over this period.

The facility was able to quickly recover from the fire and produce sellable quality product soon after the new SCADA system was commissioned.

Conclusion

Deadtime should not be a dead end. Achieving high-performance automatic control on very complex interacting loops with deadtime is possible without requiring costly software licenses. The Plummer case study proves that such an implementation meets the test of time.

About the Author

Leaders relevant to this article: